|

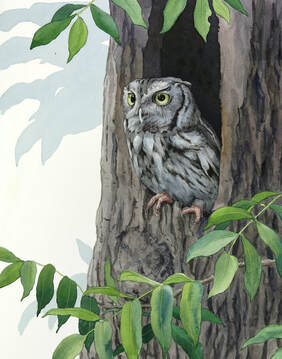

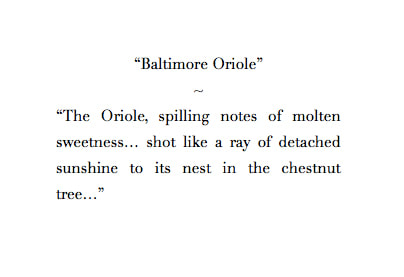

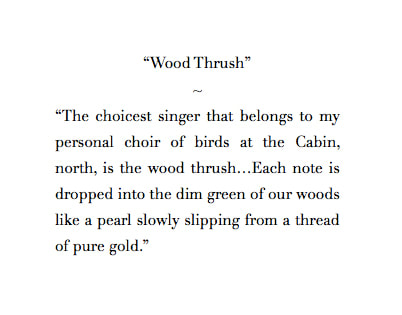

When I was young, my family and I would take turns reading chapters out of Gene Stratton Porter novels on family road trips. With characters like Elnora, a girl who hunts for rare moths in bottomland woods, and Freckles, a boy who protects trees from lumber bandits in old growth forests, her novels provided a healthy dose of flora and fauna for the nature obsessed kid. Gene was a dedicated naturalist with a poetic appreciation for the natural world, and she imbued a love for Hoosier ecology into all of her stories. This year I had the opportunity to collaborate with the Indiana State Museum and the Indiana Arts Commission to create an exhibit called The Artist-Naturalist, featuring the work of two female artists with a passion for Indiana ecology— Porter and myself. During the first half of the project I had the enjoyable task of immersing myself in Gene’s world, following in her footsteps through the Limberlost Swamp in Geneva, Indiana, and re-reading her books to gather inspiration for my paintings. The ensuing months were spent in the studio creating a series of fifteen watercolors, each based on a quote from one of Gene's written works. The paintings and quotes hung in the exhibit The Artist-Naturalist which traveled between the Limberlost State Historic Site and the Gene Stratton Porter State Historic Site from June to December, 2019. Here is a selection of paintings and quotes from the exhibit along with a video that was created to explain the project and process behind the work:

6 Comments

I like to experiment with new techniques when there’s a deadline looming. It raises the stakes, and there's added pressure to create something successful out of the experiment. When a painting begins to go south I don’t have the luxury of setting it aside. I’m forced to work through challenges and learn some of my best lessons in the process.

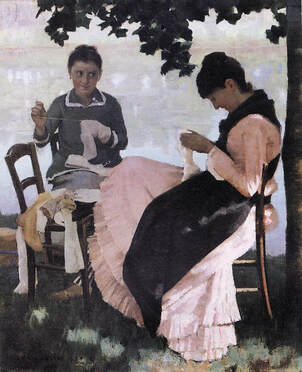

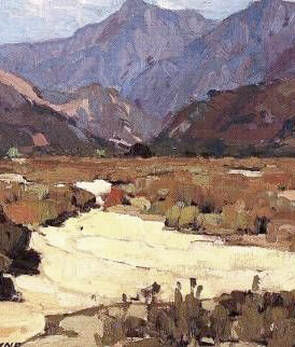

I recently conducted one of these experiments in preparation for a small works show in New Hampshire. I had a goal to stretch outside of my color comfort zone, and turned to the old masters for inspiration—Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent, Edgar Payne, etc. The colors in a painting by John Lavery immediately reminded me of a Red-winged Blackbird and rose mallow. That led me to choose a different historical painting as the initial inspiration for each of the watercolors in my small works series. Instead of using a bird as the foundation for each design, I let the colors define the composition. The birds below are the result of this experiment, and each is paired with the original painting that inspired it. “Hinterland” is a German word meaning the “land behind”. In English we’ve adopted the word to mean the unknown, the frontier, or a remote region. It’s a term we might use to describe Alaska or the space behind our refrigerator, but it’s certainly not a word we would use for the booming metropolis of Orlando—the theme park capital of the world. However, in the early 1700s when British naturalist Mark Catesby embarked on his travels through the American south, Orlando was still an unsettled pine wilderness (and would remain that way for another century).

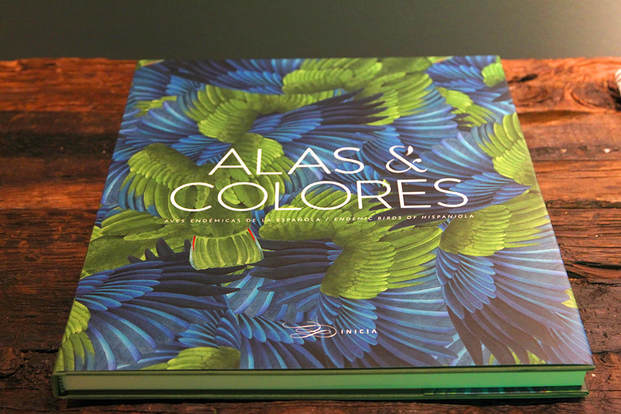

At the beginning of 2017, I received the exciting news that I was being awarded the Donald Eckelberry Endowment from The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. This endowment is given in honor of Donald Eckelberry, one of the foremost bird illustrators of the twentieth century. Eckelberry was famous for his support and encouragement of budding artists, and the endowment continues his legacy by helping natural history artists gain valuable career experience. With the help of the endowment, I embarked on a six-month project illustrating 31 endemic bird species from the island of Hispaniola. The illustrations were commissioned by the INICIA corporation for use in an educational book, website, and app. A highlight of the project was traveling to Sierra de Bahoruco National Park in search of the birds I would be painting. For the first three days we stayed in a small camp near the foot of the mountains, traveling to different locations each morning in search of my target species. There were colorful birds you’d expect to see in the neo-tropics--Hispaniolan Parrots, Parakeets, and Trogons--and there were plainer, but equally fascinating birds such as the Palmchat, Flat-billed Vireo, and Hispaniolan Pewee. My favorites of all the species I encountered were the Bay-breasted Cuckoo and the Hispaniolan Lizard Cuckoo. There's just something about cuckoos. My guide for the duration of the trip was Manny Jimenes from Explora Ecotours. Manny started an ecotourism business in the Dominican Republic after coming to appreciate the country during college road trips. He utilizes the services of locals so that money for ecotourism remains in the country and fosters an appreciation for conservation. The book featuring my illustrations, “Alas & Colores”, was released at an event in Santo Domingo at the end of the year. While the book is not available to the general public, the entire publication has been made available for viewing digitally at this link. There is also a wonderful app, “Alas y Colors”, that can be downloaded on the app store. The illustrations for the book were done on Arches 154 lb. hot press paper with transparent watercolors.

There are two brands of watercolor paper that I predominantly use—Arches and Lanaquarelle. It’s difficult for me to recommend one brand over the other since both have their advantages and disadvantages. Both brands create a quality product that stands the test of time--in this case before the 16th century. The accessibility and quality of Arches make it by far the most popular brand for beginners and professionals alike. Arches paper has a crisp parchment feel to it, with a high level of gelatin sizing that causes the color to sit on the surface of the paper. This helps create bright colors and sharp edges. This paper also holds up well to layered washes, scrubbing, scraping and general reworking of the surface. Arches makes two colors, natural white, which is a slightly warm off-white, and bright white, which is a cool white that can produce brighter colors. I prefer the natural white because it gives a muted unifying effect to my colors. While Lanaquarelle isn't found as readily as Arches in art supply stores, it is easily found through online dealers. Lanaquarelle paper has a unique “fabric” quality to the surface. It has a lighter gelatin sizing which causes the colors to sink in to the fibers of the paper rather than sitting on top as they do on Arches. Having the colors sink into the fibers creates an interesting depth, and causes the paper to feel more a part of the finished artwork. Edges become beautifully diffused when painting wet in wet on the “fabric” surface. Paintings on Lanaquarelle paper are akin to frescos where wet paint is applied on wet clay causing it to meld and became part of the final surface. Arches on the other hand is more akin to painting on gessoed canvas where the paint sits on top of the painting support. While I prefer the final quality of a work done on Lanaquarelle, these paintings take longer to execute. Because colors absorb and fade into the surface, it requires many more layers to build up value. For this reason I often find myself foregoing the preferred quality for the sake of speed and reaching for Arches paper instead.

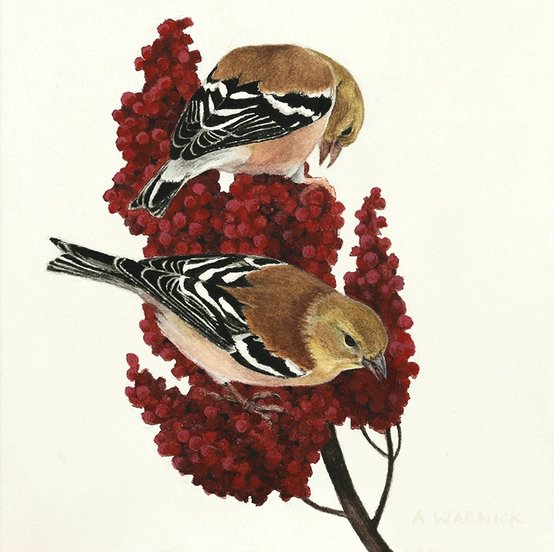

Birds have a way of making life better. They get you outside at uncanny hours to enjoy sunsets and sunrises. They bring you to new and diverse locations—city parks, garbage dumps, snowy piers, mountaintops, rocky beaches, deserts, etc. They help you appreciate what each new season has to offer, similar to how each season's harvest is appreciated by those who live off the land. Birders experience the joy of the “harvest” as Spring warblers come in, or Fall waterfowl start to amass, or (like today) flock after flock of Sandhill Cranes are constantly heard through closed windows as they travel to their breeding grounds. Noticing birds has a way of helping us notice everything else. They give us something to seek after, compelling us to see new places, meet new people, and have new experiences. In other words, they make life better. Winter is one of my favorite seasons for birding. Resident songbirds seem to become more active, and are certainly easier to see against a snowy backdrop and leafless trees. In addition we have yearly visitors from the arctic who spend the season with us in order to take advantage of our “warm weather”. I painted six of these winter birds for a small works show at the Nahcotta Gallery in Portsmouth New Hampshire: I hope you continue to enjoy the last of winter’s birds, and prepare for Spring’s approaching harvest!

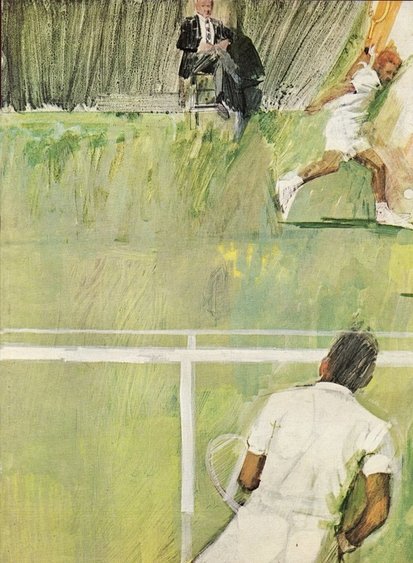

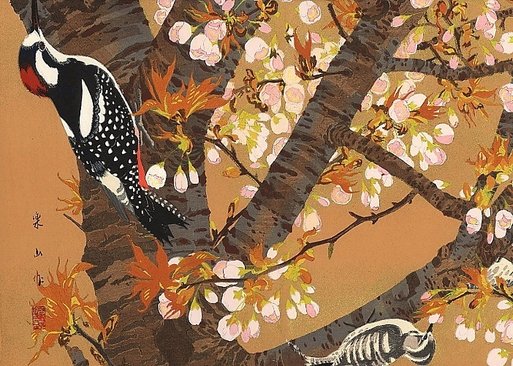

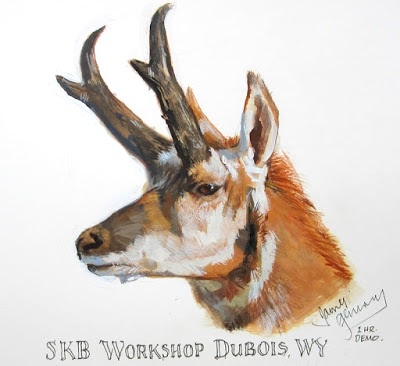

Painting is a fine balance between spontaneity and control. To spontaneously allow a watercolor wash to mingle on the paper, or leave a composition unbalanced, or create a playfully random contour line is always a gamble. Many seasoned artists learn to create perimeters in which randomness can wander, while staying within the confines of their final vision. For many of us, however, spontaneity is a difficult quality to harness. It often works against us rather than for us, and it’s easier to just do without it altogether. I struggle with insecurity when it comes to taking risks during the painting process, but constantly admire the work of those who do. Here are some examples. I love this composition by Bernie Fuchs, a 20th century commercial illustrator. Both tennis players are nearly tangent to the edge of the painting, and your eye would fall off the page if it weren’t for the strong horizontal lines repeated across the surface. This painting is energetic and captivating for the very reason that it teeters on the edge of control. Here’s a composition by Rakusan Tsuchiya using a similar method with the focal points riding the edges of the composition. Having to search for the subject becomes engaging. Bruno Liljefors was famous for his charming and random compositions that mimic the spontaneity of nature so well. Along with compositional design, creating spontaneity in mark-making is another skill that creates energy in a painting. This is one reason why children’s work is often so charming. They haven't learned control, making their art fresh and unexpected. Many veteran artists are the opposite. They’ve mastered control and then attempt to override their mechanical programming in order to create unexpected strokes. Cy Twombly built a career on this concept. This watercolor painting by Andrew Wyeth perfectly portrays the randomness found in a child’s painting combined with the obvious control of a seasoned artist. He knew how to harness spontaneity and make it work for him--from the stabs of watercolor paint that suggest the clouds in the sky, to the random spots of pure blue and yellow scattered throughout the painting, to all of the combined marks that form a grassy field without mechanically repeating vertical lines. It's the willingness to take risks that gives his work such visual impact.

One of the questions I’m most often asked is what I use for references in my paintings. I always begin a painting by gathering many different references from various sources—some from my own collection of photos and field sketches, and some from the collections of other willing photographers. Often, I’ll study similar species that might share physical characteristics, behavior, or environment in order to gather additional information and inspiration. Then, I draw a series of small thumbnail sketches without using any references in order to create an original composition that has roots in my own imagination and experience. After a basic design is reached, I piece together possible photos and field sketches that will help me construct what I envision. I take the head of one bird, the eyes of another, the posture of another, the coloring of yet another, etc., in order to devise a “Franken-bird” of my own creation. Eventually my franken-bird begins to come to life with a finished line drawing.: I begin the watercolor process with light washes of local color that I can build on. Since it's easier to dull a color with successive layers than it is to make it brighter, I lean towards a higher saturation for these initial washes. With this particular painting I experimented with a dry brush technique. Color and value were built up slowly using small amounts of dry pigment in the brush. You can see some of the finished result on the bird below. I began with a bright wash of cyan on the back and head. Then I dry-brushed darker blue over the top, allowing the cyan to peek through. The technique creates color variation in the final result. It's important not to dry-brush straight over the white of the paper or else the final color will be dull and anemic. I continued to use this same technique until the two birds were complete. Finally I added the branches and feet and stepped back to see what else would be required to finish the composition. I decided a few transparent branches in the background would create one more level of depth and not take away from the simplicity of the final design. These nuthatches are one of six small paintings (a series of winter birds) that will be shipped in March to the Nahcotta Gallery in New Hampshire for a small works show.

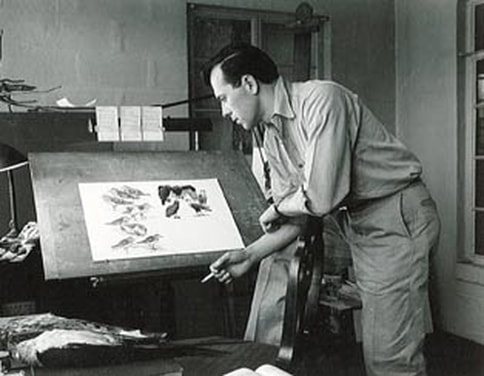

Inspired by some of my favorite bird artists of all time (Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Edwin Penny, Eric Ennion, etc.) I’ve decided to give gouache a try this year. Gouache is one of those nemesis mediums I’ve attempted to use multiple times in the past and every attempt ended in embarrassment. Here is a painting from my college days that was an assignment for a media experimentation class. We were told to render a red spherical object in light and shadow using gouache. Naturally I chose a cardinal. Hopefully this painting illustrates not only how far I’ve come in rendering birds, but also the struggle I faced with the medium at the time. With transparent watercolor, highly saturated, light-valued colors are created by allowing the white of the paper to show through. No white pigment is required. With gouache however, you add white pigment just as you would in any other opaque medium such as oil and acrylic. The trouble is that white pigment in gouache kills the saturation more than it does using any other medium. Every hue goes chalky, cool, and dull, like the colors found in a pack of Neccos. I know there is a solution to the problem, because other artists have mastered it. James Gurney and Nathan Fowkes are two of today’s artists who excel in the medium. Yesterday I decided to try a small study of a Blue-fronted Amazon Parrot, being the first bird I’ve painted entirely in gouache since my disappointing cardinal. While I still can’t seem to create the same intricacies in value and temperature shifts that are possible in watercolor, I was happy with the progress I made. Just as it takes years to master a language in order to say exactly what you want, I suppose it takes years to master a new medium. I’m invested in learning how to work gouache into my regular painting process, and hopefully you’ll see more from me soon. As 2017 begins I’m inspired by a book I received as a Christmas gift, “The Singular Beauty of Birds”, about the life and work of Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Born in 1874, Fuertes was one of the leading ornithologists and bird artists of his day. He remains a favorite of mine and many others who follow in his footsteps. His paintings strike a balance between scientific accuracy and true artistry, a feat I find challenging as one who appreciates the scientific study of birds but who also has a background in fine art. At 17 Fuertes was inducted into the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) as the youngest associate member ever. In the following years he traveled as an illustrator on many expeditions alongside scientists and researchers to the Bahamas, Jamaica, Alaska, Mexico and Ethiopia. Fuertes had a close relationship with the artist Abbott Handerson Thayer, who is most well known for his stunning paintings of angels. Thayer was also a scientific thinker and formulated a controversial theory on counter-shading camouflage among animals (You can find an interesting article here). Thayer’s wildlife portraits usually depicted this fascination with animal camouflage in a dramatic way: It’s said that Fuertes was occasionally reprimanded by his friend for having his birds stand out too much from their environment. On the other hand, his employers were often returning his work and instructing him to make the birds stand out even more. While I appreciate the skill required in a finished and fully rendered painting, sketches and unfinished work are often my favorite. A sketch is where mastery can most readily be seen. Maintaining accuracy and finesse while working speedily testifies of an artists’s skill. Fuertes displayed that finesse in his sketches, depicting his birds expertly while maintaining a freshness to the watercolor medium. “The Singular Beauty of Birds” is now out of print, but I would recommend picking up a used copy wherever you can find it. Louis Agassiz Fuertes has given us a standard to aspire to, and this book is as good as a college course for any bird artist.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed